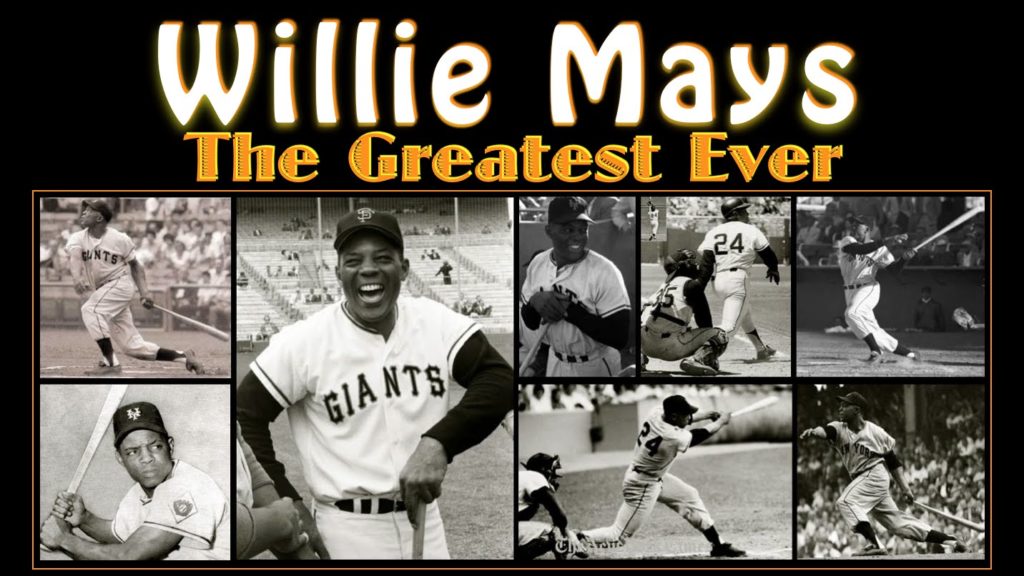

HOW WILLIE MAYS CHANGED THE FACE OF BASEBALL:

In celebration of the baseball legend’s 85th birthday, we explore Mays’s enduring spirit and his love of the sport despite facing many obstacles.-Tim Ott May 4, 2016

Willie Mays is about to turn 85. At this stage of his life, he’s an American icon, a revered ex-athlete who transcended the boundaries of his sport to become a shining example of American exceptionalism.

He’s also at a point where it’s easy to forget the fine print of his life story, a remarkable one considering that before he came along, the American public hadn’t experienced anyone quite like Willie Mays.

The baseball great was born in 1931 in Birmingham, Alabama, which means he came of age in a segregated society reeling from the Great Depression. Life was not easy, for the obvious reasons as well as those personal to his experience. Raised with little money, Mays at times went to school without wearing shoes, and he was separated from his mom when his parents split at an early age.

But Mays was also blessed in many ways. He was gifted with superior athletic genes — his dad and grandfather both played semi-pro baseball, and his mom starred in basketball and track in high school — and he always seemed to have the proper guidance in place. There were the two aunts who helped raise him as a child, and the grown men who took him under their wing when he began tagging along to his dad’s baseball games. Later, when he joined the New York Giants as a 20-year-old rookie, the team had him live with an older couple near their stadium, the Polo Grounds, and assigned a street-savvy boxing promoter to guide him around town.

Mays was also fortunate to come along when he did. In 1947, when Jackie Robinson was making headlines as baseball’s first black player in 63 years, the 16-year-old Mays was honing his skills with the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League. By 1950, following the successes of other black major leaguers like Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe and Larry Doby, Mays was ready for his turn.

Coming just three years after Robinson opened the door, the world wasn’t entirely a changed place. Mays was forced to adapt to hostile fans and separate eating and rooming facilities on minor league road trips, conditions that persisted even after he joined the Giants in May of 1951. At the time, white players were known to grumble about the increasing proliferation of blacks in the game. Even when Mays was making waves as a rookie, a cartoon in The Sporting News — a national publication — featured the young player delivering such embarrassing dialogue as “Ah gives base runners the heave ho!”

Still, the times did change, with Mays’s presence serving as an unquantifiable but definitive catalyst. For starters, there was the exuberant personality; while Robinson played with a fiery intensity borne from his burden, Mays radiated an infectious enthusiasm. His “aw shucks” persona, coupled with stories of him playing stickball with the kids in his Harlem neighborhood, suggested that he, too, was an overgrown kid, having the time of his life. It was impossible not to like him.

Then there was the sheer magnitude of his skill. Very quickly, Mays astonished opponents with his speed and powerful throwing arm, and that was before he started hitting. By the time the home runs started flying off his bat, rival executives came to realize that maybe there were more black players who could jolt a team and a fan base to life the way Mays was doing in New York.

Of course, nobody could do it like Mays. After his promising start was interrupted by a stint in the Army, he returned to win a batting title and the National League’s Most Valuable Player Award at age 23. He walloped 51 home runs the next year, then tied for the ninth-highest single-season total in history, and followed by topping the league in stolen bases for four consecutive years. Indeed, along with Robinson, Mays was credited with helping to revive the art of the stolen base, a remnant from the daring, no-holds-barred style of play in the Negro Leagues.

He’s also the author of the first widely celebrated defensive highlight in baseball lore. In Game 1 of the 1954 World Series, with the Giants and Cleveland Indians deadlocked in the 8th inning, Cleveland’s Vic Wertz smashed a massive drive to the deepest part of the horseshoe-shaped Polo Grounds. Sprinting from the crack of the bat, Mays caught the ball with his back to home plate, and quickly whirled to fire a bullet that kept the baserunners from straying too far. Remembered simply as “The Catch” — although the throw was arguably as impressive — the play helped the Giants win their only World Series over a 75-year span, and endures as the definitive example that Mays was performing on a different level than everyone else.

Mays eventually became baseball’s highest-paid player, but for all his accomplishments and fame, he was not immune to the hazards facing a black man in mid-20th century America. When the Giants moved west to San Francisco after the 1957 season, Mays had a difficult time finding someone willing to sell him a house; when he did finally move his family into one, they were greeted with a brick thrown through the window.

Furthermore, with the Civil Rights Movement gaining steam, its leaders targeted baseball’s preeminent star as someone who wasn’t wielding his influence properly. Robinson, for one, criticized Mays in his 1964 autobiography, Baseball Has Done It, as someone unwilling to speak up. “Willie has faced the same problems that confront every Negro,” he wrote. “What has he learned from life? We’d like to know.” For his part, Mays insisted he was trying to lead by example, instead of becoming a symbol of a race or a movement.

Eventually, he did become a symbol — of what happens when an athletic god plummets from Olympus. Playing out his career with the New York Mets, the once-graceful center fielder fell while pursuing a fly ball in Game 2 of the 1973 World Series. It was sad then, and the memory remains on the speed dial of any sportswriter arguing why a fading star should consider retirement.

Not that it stained the overall picture. By the time he was done, Mays had surpassed all of the established plateaus for immortality in a numbers-crazy game, finishing with more homers, hits, runs and RBIs than almost everybody else.

Furthermore, his epic career arc spanned a transformative period in both baseball and American culture. Over a quarter century, Mays played in the final Negro League World Series, became one of the majors’ pioneering black players, took center stage as the game became a televised spectacle and expanded west, and finally wound down as ownership’s restrictive reserve clause system was about to give way to free agency. He helped clear the path for Hank Aaron, another former Negro Leaguer who broke Babe Ruth’s cherished home run record, and subsequent generations of black, Latino and Asian stars in a province once exclusive to white players.

Happy 85, Willie. He may eternally be remembered as a big kid from a simpler time, but let’s also remember how far he’s come, and how he carried a stubborn old game into the modern era by being the best at what he did.

http://www.biography.com/news/willie-mays-biography-facts